|

| McDaniel-Peach House, 1910's |

First, to quickly get everyone up to speed and recap the original post, the McDaniel-Peach House is located just north of Paper Mill Road, about half way between North Star Road and Limestone Road in the development of Chestnut Valley. I had speculated that it was built sometime before 1777 by James McDaniel, who may have been a descendant of Bryan McDonald, an early MCH settler in the area near Brandywine Springs. The 1777 date sprung from a story related by Francis Cooch in the 1930's, and later compiled in the book Little Known History of Newark, Delaware and Its Environs. (I'm happy to say I found the original version of Cooch's article, printed October 16, 1932.) I believe that a few of the items graciously forwarded to me to share can shed some light on the construction of this home overlooking the Pike Creek Valley.

The first is a nearly 100 year old notation that, if correct, would slightly change this house's connection to that story of Hessian Aggression (like that?) during the march to Brandywine. (If you can't follow links, very short version: British (many Hessian) soldiers basically ransacked the house on their way to the Battle of Brandywine in 1777.) A close family friend of the Peaches (who owned it at the time), while on a visit in 1921, wrote in her address book, "Will Peach's house was built in 1782. The name on the datestone M & J McD. Mary & James McDannell." As far as the name goes, it confirms that it was James McDaniel who built the house. And "McDannell" seems like a plausible intermediate step between McDonald and McDaniel. The questions come with the date.

Obviously, if the house was built in 1782, it wasn't there to be ransacked by Redcoats in 1777. I can think of three possible explanations. The first is that the 1782 date is wrong. Although it's not clear if the date itself was on the datestone (sometimes they were just initials), I have no reason to doubt its accuracy. It's a pretty specific date and the house had basically stayed in the same family, so I'm inclined to take it at face value. A second possibility is that the house actually was built prior to 1777, and that the 1782 date memorializes a renovation or reconstruction of it. The third possibility I see is that the current house really was built in 1782, replacing an older one on the site. It would have been the older one, then, that was plundered by the British.

| McDaniel-Peach House today |

And as for the house itself, whenever it was built, I can now make a better assessment of it thanks to an old picture. I can also see that my original supposition was incorrect. The photo at the top of this post shows the McDaniel-Peach House as it looked around the early 1910's. Compare that to the current configuration of the house, as seen above. Without a good look at the home, I had guessed that the eastern part (on the right - the house faces south) was the original section. The old picture clearly shows that the western end is the oldest part of the house. I also think it shows that there have been several phases in the construction of the house. If you look closely at the old picture, you can see a line running down the roof, coming down to the near end of the two-story bay. That, combined with the seemingly interior chimney, leads me to believe that the section where the bay is was added at a later date to the original western portion. And since the three windows on that block don't seem to be symmetrical, it's possible that there was more than one phase to that part, as well. The entire eastern wing does not appear to be present in the 1910's photo (nor does it seem to be in the 1937 aerial shot, but that's very difficult to tell), so it must have been erected later. There's also a rear wing on the western end, but the old picture doesn't include that area so I can't be sure of its date. I would think it would be 19th Century, but it could also have been built at the same time as the eastern wing.

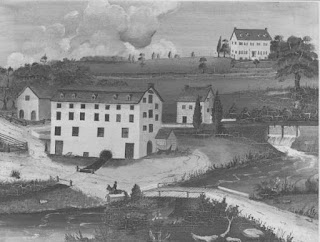

The final thing I wanted to share was a picture not of the house, but of the industry that was undertaken on the property for several decades -- kaolin mining. As with several other properties in and around Hockessin, kaolin clay was discovered on the Peach farm in the late 1800's. After discovering the valuable clay on their property in 1893, William Paul Peach and his siblings soon went about extracting and processing the material. They built a plant on-site and by 1899 had 35 people in their employ. The picture below is of the processing plant, circa 1920. The Peach family sold the business to an outside firm in 1916.

|

| Peach Kaolin Clay Company |

I have been unable to find any mention of exactly where the plant was, or from where the clay was mined. One source puts the plant "along Pike Creek", but I think that's a more general description of the property than of the plant. From studying the the 1937 aerial photos of the area, though, I think I might have a guess or two. I'll lay them out and see what everyone else thinks.

| Peach Farm, 1937 |

I've also spent a good amount of time staring at the clay company picture, too. I can't find anything definitive to tell me exactly where we're looking, but I have a theory (yes, of course I do). Since the picture was taken by someone visiting the house, it makes sense that they would have been coming from there. I think the picture is looking south, with the house somewhere behind the photographer. This would put Paper Mill Road possibly on the other side of the trees beyond the structures. Interestingly, if this is true, then there's one other identifiable structure. In the upper right, you can see a white building. If the picture looks the direction I think it does, then this structure could be the large barn built by Abel Jeanes in 1832.

In any case, these new pictures and documents give us a bit more information about this historic property. I want to thank the contributors very much for passing these along to us.

Harry Riblett is my Dad. He is a published author and consultant on airfoil design. He and his brothers are pilots by hobby. I can remember my Uncle Richie landing helicopters...

Anonymous December 4, 2012 11:11 AM

Interesting. As a Dempsey, it is very interesting to learn the history.

Larry T November 27, 2012 7:35 PM

I also grew up in Sherwood 2, I must be older than Vic C. The property on both sides of McKennans used to be state property/ prison farm. After closing the prison farm, the state sold...

Scott P November 27, 2012 10:07 AM

Thanks, Vic. Good to know. So unless the house was small and overgrown, then it sounds like the barn lasted longer than the house did. In either case, it...

Anonymous November 26, 2012 12:45 PM

I grew up in Sherwood Park II. I don’t remember the house but I do recall an old barn back there. Older kids would go there to smoke. We roamed about the overgrown fields quite often. It was...

Anonymous November 24, 2012 12:02 PM