|

| James Annesley, one-time MCH resident |

Many of you may be familiar with the 1886 Robert Louis Stevenson novel Kidnapped, which has been adapted for movies and television at least a dozen times over the past century. It's the story of a young Irish boy, recently orphaned, who discovers he's heir to an estate. Before he can take possession of the estate his evil uncle has him kidnapped to be sent off into servitude in the Americas. The boy escapes after his ship wrecks off the coast of Scotland, has a series of adventures across the Highlands, and eventually gets his inheritance back from his uncle. Stevenson's "boy's novel" has, over the years, become much beloved by readers everywhere.

As thrilling as the story is, what's really amazing is that it may well be inspired by a true story. In real life the boy, also an Irish orphan set to inherit an estate, did actually get sent to the Americas as an indentured servant by his uncle. The most intriguing part of it for us, though, is that the boy in question, James Annesley, spent many of his servile years right here in Mill Creek Hundred.

James Annesley was reportedly born April 15, 1715 (we'll have to remember to celebrate his 300th this time next year -- someone else can bring the candles) to Arthur Annesley 5th Baron Altham. The Annesly family history is rather complex, but the short version is that they were an English family that became prominent and wealthy in the 1600's in Ireland and the home isle. All looked good for them until the early 1700's, when due to numerous tragic deaths and other circumstances the family title passed out of the main line and to a ne'er-do-well younger cousin. This was James' father.

The young Arthur abandoned his wife, then reconciled long enough to produce James. Soon after he threw her out on false charges of adultery, then threw eight-year-old James out onto the streets. When Arthur died in 1727, his younger brother Richard moved in to take over the title and estate. If anything, "Uncle Dick" seems to have been a worse person than his brother. Seeing that young James (then called "Jemmy") could be an impediment to the inheritance, he had the boy kidnapped and sent to America.

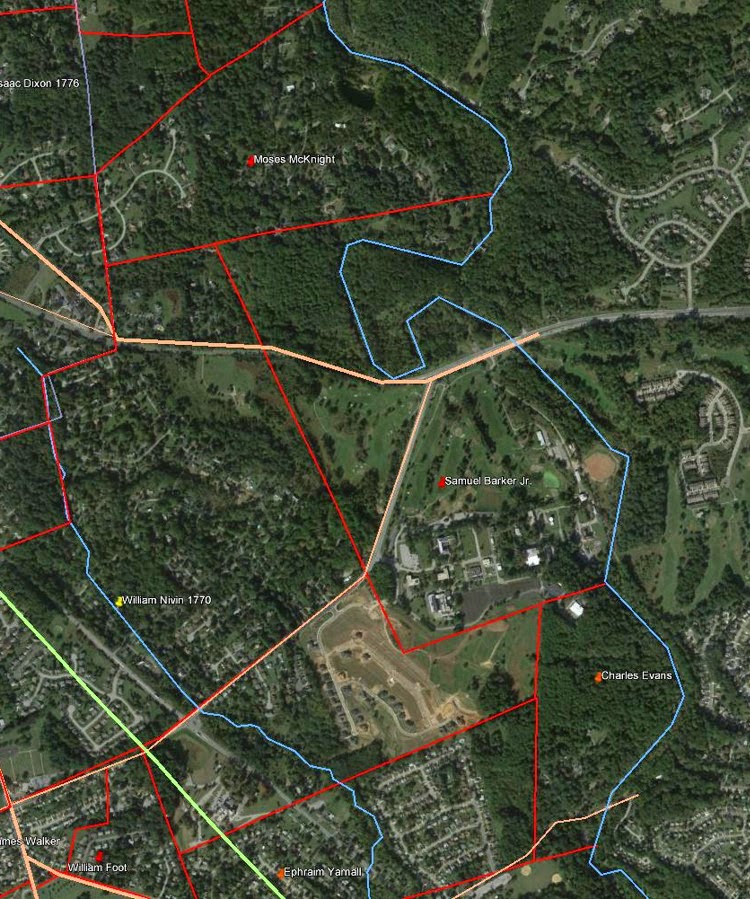

On April 30, 1728, Jemmy was abducted at Dublin's Ormond Market and stuffed onto a ship (ironically called the James) bound for what was then a thriving port -- New Castle. After arriving in New Castle, James was purchased by a small-time farmer and taken away. This is where it gets interesting for us, because his new master was Duncan Drummond of Mill Creek Hundred. Annesley spent 12 years essentially as a slave in America before returning home to fight for his rightful inheritance. Thanks to the transcripts of his court case (a sensation at the time) and a version of the tale published in a contemporary newspaper, we have a pretty full account of his time in the colonies.

As mentioned, James' first master was Duncan Drummond. We know a little about Drummond, but not quite enough. Thanks to several sources (including Walt), we know that Drummond was close to the Robinson family of Milltown, and about this same time purchased around 110 acres from George Robinson. This tract extended eastward from Mill Creek, somewhere between Milltown and Stanton. The other question probably on everyone's mind I can't quite answer for sure -- was he related to Polly? My guess is that Duncan was likely an ancestor of Polly's husband James, maybe his grandfather or great-grandfather. As of yet, though, I haven't found the smoking gun that would prove it.

But getting back to the young James Annesley, it seems that Drummond was not a very good master. He beat James and generally treated him poorly. James reportedly retained his dignity throughout the ordeal, knowing his status and always believing that one day he'd return home to claim what was his. He probably saw himself as being "above" the other servants, and as a result mostly kept to himself. The one exception was an older female servant -- herself a victim of a kidnapping -- who had received a bit of schooling. James befriended her and she acted as his teacher, at least whenever Drummond wasn't looking.

|

| James Annesley, c.1750 |

After about four years, though, James' friend died and he'd decided he'd had enough. He ran away, but fate was not to smile upon him yet. The whole story is recounted here, but the short version is that he fell in with some people who were going to help him, but it turned out they were accused thieves. The group was caught and taken to the jail in Chester. The others were condemned to death, but James was able to convince the judge of his innocence. He was still held, though, displayed every day in the marketplace to see if anyone had seen him in Chester before. After five weeks of this, Duncan Drummond happened to be in town on business, recognized his escaped slave, and took him home. As a result, two extra years were tacked on to the two that had been remaining on his servitude.

After returning home (where, exactly, I frustratingly don't know), Drummond's treatment of Annesley became even worse. James complained to the court in New Castle, and Drummond was forced to sell him to a new owner. Here lies another hole, as none of the accounts I've seen mention the new owner's name. Whoever it was James survived another three years with him, until a chance meeting with some sailors bound for Europe. With his ambitions thus spurred on, James attempted another escape, but this one was no more successful than the last, except that he was recaptured without a prison stop.

After returning again to captivity, James became so depressed that his master took pity on him and assigned him to his wife's care. This also happened to include the care of the master's daughter Maria, who soon fell in love with him. And she wasn't the only one. Another slave, an Iroquois girl named Turquois, also became quite smitten with him. Ok, maybe more than smitten. (Must have been the brooding and the accent. There's no competing with brooding and an accent.) It seems James politely rebuffed both girls, but the "Indian girl" didn't take it so well. One day she confronted and attacked Maria, then in a fit of anger, despair, and maybe remorse threw herself into the nearby river and drowned.

As you might expect, the master was not happy to have lost a servant and nearly a daughter, but after hearing everything out determined that James was innocent of any wrongdoing or inappropriate behavior. To keep the peace and appease his daughter, he promised to set James free. However, after taking him to Dover he instead sold the Irish young man to a planter near Chichester. After some time with this master, James was transferred to another owner "whose house was almost within sight of Drummond's plantation". With more research, we might even be able to determine where he might have been.

|

| Annesley Hall, which I think was James' ancestral home in England |

Amazingly (or maybe not so amazingly, considering that much of this came from a magazine story), James' adventures were not over. Soon after arriving at his new home, he was tracked down by two brothers of Turquois, the spurned Iroquois maiden. They were looking for revenge from Annesley, but he managed to fight them off and narrowly escape. Soon after, he happened to overhear a plot between his mistress and a neighboring servant to rob his master and flee together to Europe.

Instead of going to his master, James confronted her and threatened to expose her if she didn't change her plans. She did (for the time being), and apparently tried to "win over" James. I don't think she was a very good wife. After failing in this, too, she tried to poison James, who survived only because a cat accidentally ate the tainted soup and died before his eyes. Having never abandoned his desire to return to Ireland, and even though his period of servitude was nearly up, he made one last attempt to escape.

This time, unlike the previous attempts, the now 25 year old Annesley was successful in gaining his freedom. He boarded a merchant ship to Jamaica, where he made his way onto a British warship which returned him to Ireland. He set about regaining his birthright, which he did after what was at the time one of the longest trials ever seen in Ireland (15 days). Of course, on par for the story, this was only after successfully defending himself from a murder charge after killing a man in a hunting accident.

I apologize for the length of this post, but you really have to hear the whole story to fully appreciate it. For many years much of James' story was dismissed by historians as fiction, a tale exaggerated for the reading audience at the time. Recently, though, the work of history professor A. Roger Ekirch shows that there is far more truth to it than previously assumed. Could some of Annesley's colonial adventures be a bit padded? Sure, but many of the basic facts seem to hold up, and to me it's fascinating that much of the story took place here in Mill Creek Hundred. If we're ever able to more closely pin down some of the locations, I'll be sure to pass them along.