![]() |

| The Justis-Jones House |

In the recent post about the McComb-Winchester House I teased about a link between its most prominent owner, Henry S. McComb, and Mill Creek Hundred. That link comes in the form of the house seen here, the Justis-Jones House. It's situated on the west side of Newport-Gap Pike, just south of and up the hill from Brandywine Springs. It's one of those houses that lots of people probably see and think, "Gee, that's got to be an old house," but know nothing about. Although not the most flashy of homes in the region, to me it has its own air of dignity. It also happens to be somewhat unusual for the area in two major respects.

First, unlike most of the remaining houses from the first half of the 19th Century, it was never the manor house of a large farm or estate, and was only ever briefly occupied by its owner for much of its first 60 or 70 years. The second difference is in what is known about it. Whereas it seems with most sites that we're digging to find a scrap here and there about any owners we can, much research was done into the ownership history of the Justis-Jones House. This is one of the last sites in MCH listed on the National Register of Historic Places that I've gotten to here on the blog. It's NRHP nomination form has an almost mind-numbing amount of information about the various owners of the house. Needless to say, I'll just do a brief overview of its history, hitting the major points. Later on I'll provide a link the the NRHP form if anyone wants the whole story.

The story actually begins with a member of a very prominent local family covered in several earlier posts (

here and

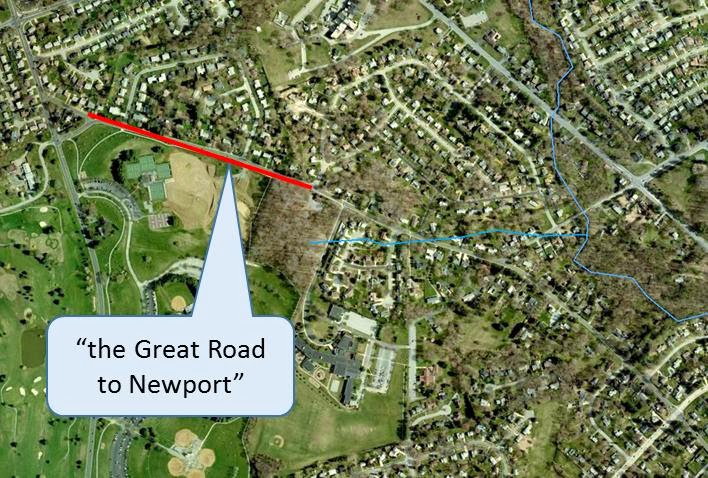

here) -- the Justis family. David Justis (1797-1843) was the youngest of three brothers, sons of Jacob Justis. About eight years after Jacob's death in 1802, his estate was divided between David, Joseph, and Justa. At that time the Justis land stretched from Red Clay Creek on the east, from Hyde Run south to the Philips (Greenbank) Mill property, and westward a ways down Milltown Road. Joseph's part is not clear, but Justa (later builder of the original Brandywine Springs Hotel) received land to the west of the (then proposed) Newport and Gap Turnpike, while David inherited the core of the homestead to the east of the road.

David Justis was still a boy when his father died, and was subsequently cared for by a series of relatives and family friends, including for a time

Thomas Justis at his house just to the west. Eventually he moved into what was probably his father's log home and sometime between 1828 and 1837 added a stone section to it. This house was located very near (if not exactly on) the site of today's White House B&B (an early 20th Century home) south of the Cedars. Sometime before 1836, and maybe as early as the early 1820's, David purchased from his brother Justa six acres on the west side of the turnpike. It would be on this tract that the Justis-Jones House would be built.

The house was not built right away, however, and tax records indicate that as late as 1837 it was still not present. Sometime in the next few years -- and certainly prior to his death in 1843 -- Justis had the house constructed. The original section of the house is a two-story, two-bay stone home measuring about 22 feet wide by 25 feet deep. Today stucco covers all of the house except for the front of the second floor, but evidence seems to show that originally the entire house was exposed stone. The stucco was likely added in the 1860's by an owner we'll get to shortly. Several additions were added in the early 20th Century, including an enclosed front porch, a two-story frame rear addition, and a two-story bay window covered with fishscale shingles.

![]() |

| Some of the underlying stone visible from the side |

Now that we've covered the "What" of the house, we get to the "Why". The

National Register of Historic Places form, completed in 1998, contains a great deal of detail about the architecture and features (inside and out) of the house, often comparing them with similar houses in the area. You're more than welcome to peruse the entire thing, but the gist of it is that the house David Justis built was a good, upper-middle class home. It had some of the features of the larger homes nearby, but not all of them. It's nice, but not overly fancy. The reason for this is probably that Justis wanted a house that reflected well on someone of his standing, but it didn't have to be spectacular because it was never meant for himself or his family. It was strictly a rental house, one that may have been built with a particular person in mind.

The small, six acre lot on which the house stood meant that it was never going to be a profitable farm property, but that was fine because the next owner was not a farmer. In 1843, shortly before his death, David Justis sold the new stone house and six acre lot to Thomas W. Jones for $600. Jones was a cordwainer (shoemaker) most recently residing in Stanton. Three years earlier Jones and wife Hannah purchased a brick and frame house* in the village for $800 from John Foote (mentioned in

the post about his family). He sold it in 1842 for $1000, then bought this house from Justis in 1843. There is good evidence that the three men (Justis, Jones, and Foote) all knew each other (possibly from attending St. James Episcopal Church), and that Justis may have built the house with Jones in mind.

There is some speculation that Justis may have built the house as a farm tenant's residence, or that Jones may have worked in a mill, or that it served as a toll house. There doesn't seem to be any evidence, however, that it was meant as anything other than a place for Jones to live and carry on as a shoemaker. He even did work for Justis himself, as a $7.60 shoe work debt to Jones, submitted to Justis' estate, shows. Thomas Jones even bought several items from Justis' estate sale, and probably moved into the house about the same time.

After moving in, Jones modified the interior layout of the first floor, changing it from a double-cell to a side-passage plan, which was more in style at the time. Unfortunately for the shoemaker, he wasn't in the house to enjoy it for long. Whether he overextended himself on the renovations or just hit a patch of bad luck, by 1849 Thomas Jones shows up on a list of delinquents in MCH. Not only did he owe money to Justis' estate, Jones also still owed money to John Foote for the Stanton property. The Sheriff seized the property and it was sold in October 1850 for $1100, to

Henry S. McComb. Thomas W. Jones may have moved then to Wilmington, but sadly there's not much information to show he ever got his situation turned around.

McComb owned the property for 18 years, but of course did not live there. While he resided in his mansion at 11th and Market Streets in Wilmington, the house on the turnpike was just one of many real estate investments for the leather manufacturer and railroad entrepreneur. In addition to the Justis-Jones House, McComb owned numerous other properties including

a large estate in Claymont, later to be the site of the Brookview Apartments and now (eventually) Darley Green.

It's not clear who lived in the house during McComb's ownership, although further study could provide some clues. It may have been an artisan like Thomas Jones, a worker in one of the local mills, or a farm hand on a nearby property. Interestingly, in several tax assessments during the period, the house is described as being of frame construction. This is likely due to confusion stemming from the new stucco covering applied by McComb in an attempt to make the house more "modern".

The next owner of the house was George M. Bramble, who bought it for $1850 in 1868. Bramble lived in Christiana Hundred at the time, a self-professed "cooper and farmer", but appears to have moved into the Justis-Jones House around 1870 for a few years. The 1870 Census finds him here, as does an 1871 assessment. His occupation is listed as "trucker", which could explain his interest in a house situated on the turnpike. Bramble didn't stay here long, though, and seems to have moved permanently back to Christiana Hundred by 1873.

The house was undoubtedly rented out for the remainder of George Bramble's life, which came to a close in 1890. After his death, the house returned to the McComb family, as Henry's widow Elizabeth recouped the property because of debts owed to her by the late Bramble. After reacquiring it in 1892, McComb sold the house in 1893 to John O. McFarland. He, too, eventually fell behind on his debt, and in 1901 Jane McComb Winchester (Henry's daughter and then owner of the Wilmington mansion) again acquired the property.

![]() |

| 1912 Plan for The Cedars and Hilltop |

The McCombs finally unburdened themselves of the property later that year, when it was sold to George F. Thorp. Thorp sold the house in 1904 to Harry W. Sherman, who would live there until 1915. Sherman would change the property forever. For one thing, about 1907 he added the first frame wing (one story) on the rear, the bay window, and the front porch. More importantly, Sherman divided up the property into smaller lots. With

The Cedars selling lots as early as 1901 across the road, Sherman may have had this in mind as a real estate venture from the beginning. In 1907 he began selling lots, at first empty but later with homes already in place. The lefthand (unnumbered) larger lot contained the Justis-Jones House, next to the rest of what Sherman called "Hilltop".

The lot containing the house was sold by Sherman in 1915 for $2900 to Lida Reynolds of Wilmington. It appears Reynolds rented out the home for her 9 years of ownership, as she and her husband continued to reside in Wilmington. She sold it in 1924 for $5000, the higher price probably reflecting the additions of the second floor on the rear wing, a newly-installed bathroom, and the garage.

The house went through a number of different owners during the 20th Century, including the Wilkinsons, Smeads, Smiths, and several others. Although its parcel has shrunk, the house itself continues to look much as it always has. One of the recent owners removed the stucco from the front of the second floor, which even though it's the only place with exposed stone gives the appearance that it all is when you drive by. Even though it's not the only historic house in the area, the fact that it was mostly used as a rental house and that it was owned by an artisan (as opposed to a farmer) does make it somewhat unique. It appears to be in very good condition, and stands as a link to the changing nature of Mill Creek Hundred in the mid-1800's.

Additional Facts and Related Thoughts:

- As seen in this DelDOT report (Page 17 of the PDF), the lot Jones purchased in Stanton was on the northwest corner of Limestone Road and Main Street, where St. Mark's Methodist Church is now.

- Thomas W. Jones' son, Thomas W. Jones, Jr., went on to become a miller. He owned a farm near McClellandville north of Newark, and also later purchased the England (Red) Mill on Red Mill Road. It was he who built the tall addition to the mill in the 1880's. He may also have been the resident miller at the Stanton Mill around 1860.

- Again, here is the link for Nation Register of Historic Places nomination form. Here are the photographs.

After a short absence, the Mid-Week Historical Newsbreak is back, with a story about a holiday season tragedy in Stanton. This one is interesting because it started out as just a short posting, but the more I found out the more I'm thinking that it might have had repercussions that are still evident today. I found several similar but slightly different newspaper accounts of the incident, each one providing a bit more of the story. The one seen above gives the short version of it, being that three people (well, two and a third assumed) were killed when they were struck by a train in Stanton. Sadly, it's a story that you can still see in the paper once or twice a year nowadays it seems, but this one may have a little more to it, I have a hunch.

After a short absence, the Mid-Week Historical Newsbreak is back, with a story about a holiday season tragedy in Stanton. This one is interesting because it started out as just a short posting, but the more I found out the more I'm thinking that it might have had repercussions that are still evident today. I found several similar but slightly different newspaper accounts of the incident, each one providing a bit more of the story. The one seen above gives the short version of it, being that three people (well, two and a third assumed) were killed when they were struck by a train in Stanton. Sadly, it's a story that you can still see in the paper once or twice a year nowadays it seems, but this one may have a little more to it, I have a hunch.