|

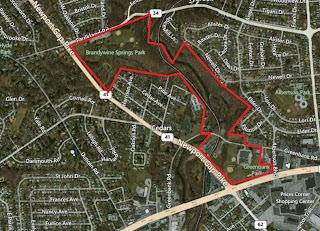

| General outline of the Red Clay Creek Corridor Park area |

Unknown to most (or at least until recently, to me), there was at least one other potential plan floating around during those high-flying Ford Years. I have no idea how seriously this plan was taken, or whether it ever had any real chance of being implemented. My gut feeling is that this was strictly a "Let's see what we can come up with on the ambitious end of things" kind of plan, and I have a hard time imagining it being adopted. And even if it had somehow miraculously been adopted, the continuous funding and effort it would have entailed would have made it an easy target any time budgets needed to be trimmed. Even with the strongest of supporters, I couldn't see most of the plan lasting very long.

So what are we talking about here, exactly? I've uploaded the plan here, so if you're interested go take a look. It's not as long as it first seems, and it's not hard to read. It doesn't get too technical or infrastructury, outside of a few mentions of water and sewer hook-ups. The plan is really more of a general concept of how to link the parks, along with a few properties in between (although it does give a list of costs at the end). Good luck trying to imagine what the area would be like with this Red Clay Creek Corridor in place! I do know that as a young child at that time, I think I would have loved it.

Rather than trying to properly recount and analyze the plan, I'm just going to bullet-point some of the main features and let you read and fill in the blanks. I do really wish there had been drawings of what they had in mind, though.

- Mulched pathways would connect Greenbank and Brandywine Springs along Red Clay Creek, passing through the Greenbank Mill property.

- Albertson Park would be included. Albertson Park is essentially land north of Greenbank along the east side of Red Clay. The Kiamensi Spring Water Company site would be cleared and developed as "a point of interest".

- A motorized tram would run between Greenbank and Brandywine Springs along paved paths to be built. The tram would be "the trackless type consisting of a motorized power unit and several coaches." I'm picturing something like an over-sized golf cart pulling cars, like you'd see as a parking lot shuttle at amusement parks (at least they used to have things like that -- I haven't been to a park in while).

- I don't think it states when or how frequently the tram would operate. I would imagine only in spring/summer/fall, and/or only on weekends.

- Greenbank Mill, which was still in a poor state at the time (only a few years after the devastating fire), was to be renovated and restored, along with its accompanying water system. The mill was owned by Historic Red Clay Valley, Inc. (also operators of the Wilmington & Western) at the time, and I can't quite tell whether the county would be purchasing the mill, or granting money to HRCV to do the restoration as a partnership. The area around the mill was to be developed as a pedestrian plaza and tramway drop-off point, highlighting its historic aspects.

- The northern terminus of the tramway would be Brandywine Springs Park, which would see its highest level of action and construction since the early 20th Century. The tram would drop off at the area near the chalybeate spring (the Spring Garden), before looping around the to-be-restored lake and heading back to Greenbank. (Incidentally, the Friends of Brandywine Springs (FOBS) has been working for about a decade and a half to get the lake restored, and still the county has not gotten it right.)

- A children's amusement area was to be built across Hyde Run from the Spring Garden. "The proposed amusement devices will reflect the early 1900's era. The rides are to include a carousel, swings, ferris wheel and devices." On the one hand, elementary school-aged Scott would have LOVED this. Grown-up "historian" Scott shudders to think what archeology would have been lost, since this would have sat right along where the old boardwalk ran during the amusement park era.

- I don't know if this plan got as far as public debate, but if it had I think it could have gotten ugly. When FOBS was formed in the early 1990's, some residents in the Cedars loudly raised objections to any plans of "rebuilding" the amusement park, which is practically (and sometimes literally) in their backyard. Nevermind the fact that FOBS never had any desire to do such a thing, nor ever even raised the subject. Now after reading this report, I wonder if this is where those objections originated.

- The upper part of Brandywine Springs would have been relatively unchanged, with just some more parking, another pavilion, and some enhanced trails and historic markers.

- Greenbank Park would have seen several large changes from what actually occurred. Naturally, the tramway would connect the different sections of the park.

- One section would contain an Activity Center, which would have space "for meetings, recreation, cultural arts and sales, rest rooms, maintenance, and for other suitable purposes." It was to be housed in an existing building, but I'm not sure what building that was.

- A mall and entry plaza would provide a focal and gathering point for the park, and serve as the tramway terminal.

- Greenbank Park would be home to a 5645 sq. ft. "Z"-shaped swimming pool. A pool building would house changing areas, ticket office, rest rooms, and maintenance and mechanical rooms.

- A playground would be next to the children's wading pool, and would contain "a timber climbing device." Sounds like the playground equipment that used to be at Brandywine Springs.

- Much of the rest of the park would have been developed similarly to how it eventually was. It was to have tennis courts, basketball courts, and handball courts. There would have been one baseball field instead of two.

- There was to be a display and courtyard around the watchtower.

- In the lower section of the park, the little league field would remain and the Wilmington & Western station area would be upgraded. Here also would be additional parking for the WWRR, the Greenbank Mill area, general park visitors, and the amphitheater.

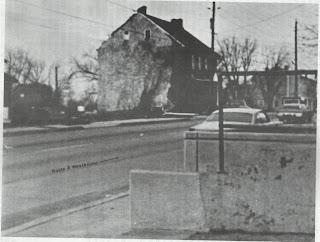

- Finally, an open-air amphitheater would be built on the north side of Greenbank Road in the open area below the brick "Warden's House".